Have you ever wondered why the world around us smells the way it does? From the earthy scent of rain to the inviting aroma of freshly baked bread, many of the smells we encounter daily are actually created by microbes.

Consider the scent of a ripe cheese or a glass of wine—these aromas come from bacteria and other microbes. Even less pleasant odours, like old sweat, smelly feet or a mouldy apple, are thanks to molecules produced by microbes.

Let’s explore the fascinating world of bacterial smells, their origins and what we can learn from them.

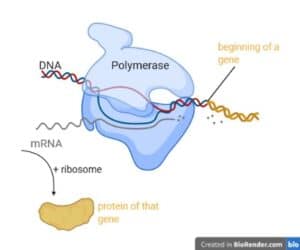

Microbial smells come from volatile organic compounds

All microbes produce volatile organic compounds as part of their metabolism. These molecules are generally gaseous and vaporous, allowing us, animals and even plants to smell and react to them.

Depending on their environment, the substrate they use, pH, salt concentration and temperature, microbes produce various volatile organic compounds. These can range from simple gases like carbon dioxide or ammonia to organic acids such as isovaleric acid or large and complex steroid derivatives.

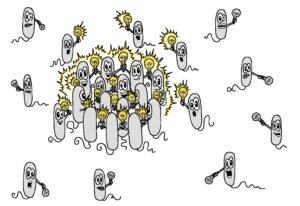

For both microbes and us, volatile organic compounds serve as a means of communication and information. As we’ll see, these small compounds play crucial roles in microbial communities and their survival. On the other hand, for us, certain volatile organic compounds signal to our brains that bacteria are present, indicating that something may not be safe to eat or drink.

Some bacterial odorous molecules have a dual nature: indole, produced by gut bacteria from food, gives faeces its characteristic odour. Yet, at low concentrations, indole has a flowery scent and is even used in perfumes.

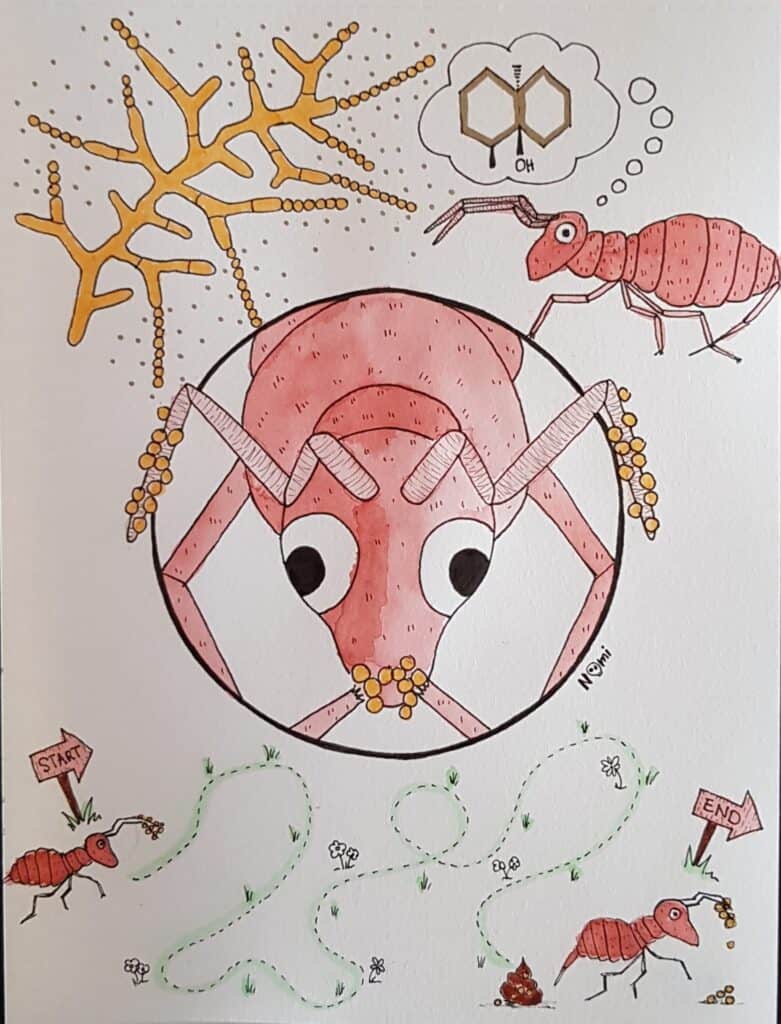

Bacteria attract animals with earthy smells

Do you recall the scent of fresh rain? That earthy, musty smell comes from a molecule called geosmin, produced by bacteria of the Streptomyces family.

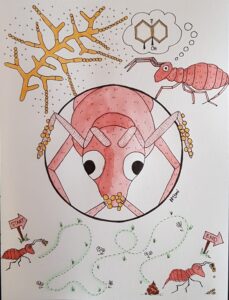

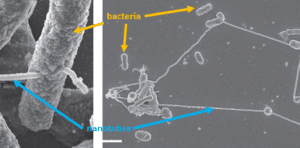

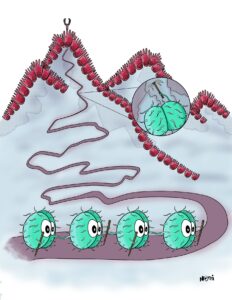

Streptomyces live in the soil, where they produce soil material and form long thread-like filaments. To survive and spread, they use the volatile organic compound geosmin.

When these bacteria release their spores into the soil, they cover them with both antibiotics and geosmin. While the antibiotics protect the spores from other microbes, geosmin attracts small insect-like animals. These creatures eat the spores and distribute them in the environment.

In this case, geosmin signals a food source to the animals as the spores nourish the animals. At the same time, the spores use the animals for transport to new areas. Once conditions improve, the spores develop into bacteria and start forming their filaments in the soil.

Also mosquitoes are attracted to the smell of geosmin in ponds and waters. Here, cyanobacteria produce the molecule, so the mosquitoes decide to lay their eggs here as the bacteria are food sources for the larvae.

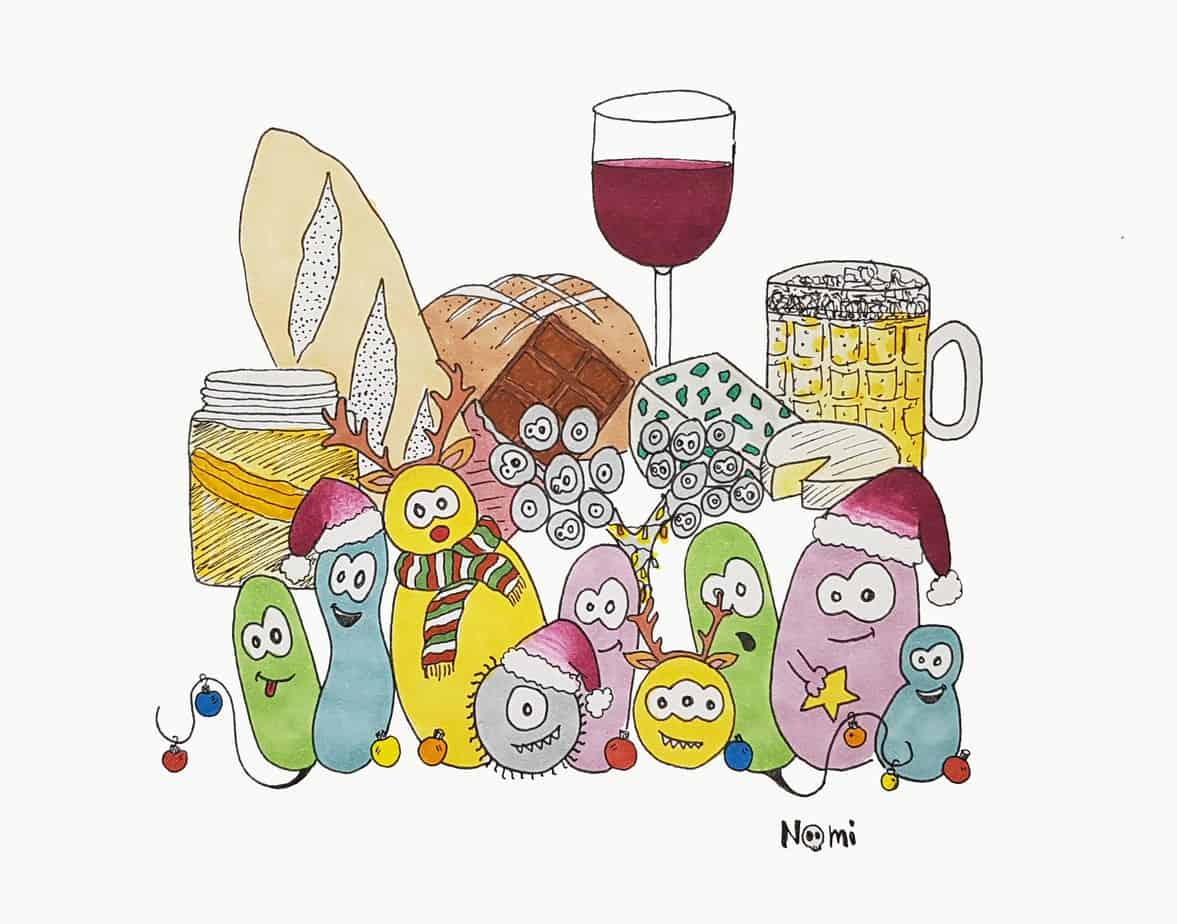

Bacteria produce characteristic food smells

Other pleasant and unique bacterial smells come from the fermentation of fruit, vegetables or milk. During this process, bacteria produce compounds that give food not only their characteristic tastes but also aromas.

As an ancient fermentation product, vinegar has a very characteristic sour smell due to volatile organic compounds produced by microbes. Mainly bacteria from the Lactobacillus and Leuconostoc families and some yeasts degrade the sugars of cereals or fruits to produce acids and alcohols.

Also, the fine aromas of wine and cheese come from the many volatile organic compounds bacteria and yeasts produce during fermentation. They include alcohols, aldehydes, ketones, lactones, esters as well as many other classes of chemicals. As you probably know, depending on the origin of the grapes or milk, the ripening temperature and the microbes added, the resulting product can taste and smell entirely different.

However, the unpleasant smell of rotten foods is also due to bacterial metabolic activity. Meat, fish and eggs contain molecules like choline and trimethylamine oxide. Over time, bacteria break these down into trimethylamine. Your brain likely recognises this off-flavour as a sign of food decay, triggering you to reject rotten foods to protect your health.

Bacteria create your unique body odour

Interestingly, your body odour changes based on what you eat and which microbes and bacteria you introduce into and onto your body. Depending on your diet and health, your body secretes different mixes of sweat—generally a watery mixture of minerals, amino acids, fats, urea and antimicrobial substances.

Although your skin produces odourless sweat all over the body, some areas are more hospitable for bacteria and microbes than others. Consider your armpits, where your main body odour originates: They contain more sweat glands and slightly different hair follicles, making them moister and more enclosed. With more water and nutrients available, your armpits are very microbe-friendly.

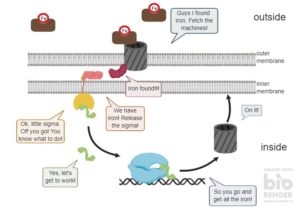

Consequently, the microbial communities in your armpits can differ completely from the rest of your body. Here, three bacteria—Corynebacterium striatum, Corynebacterium jeikeium and Staphylococcus haemolyticus—have special strategies to survive the high salt content of sweat and even use the urea in sweat as food.

They break down the molecules in sweat into volatile organic compounds that together give each person their unique body odour. For example, sulphur-containing compounds, often with strong onion-like smells, are produced by Corynebacteria.

Our sweat also contains lactic acid and glycerol, from which Staphylococcus and Propionibacteria produce acetic and propionic acid. These molecules directly impact your body odour as they evaporate leaving a pungent smell or supporting the growth of other bacteria. But our smelly sweat has advantages too: After eating citrus fruits, people’s sweat contains limonene, a mosquito-repellent possibly generated by skin bacteria.

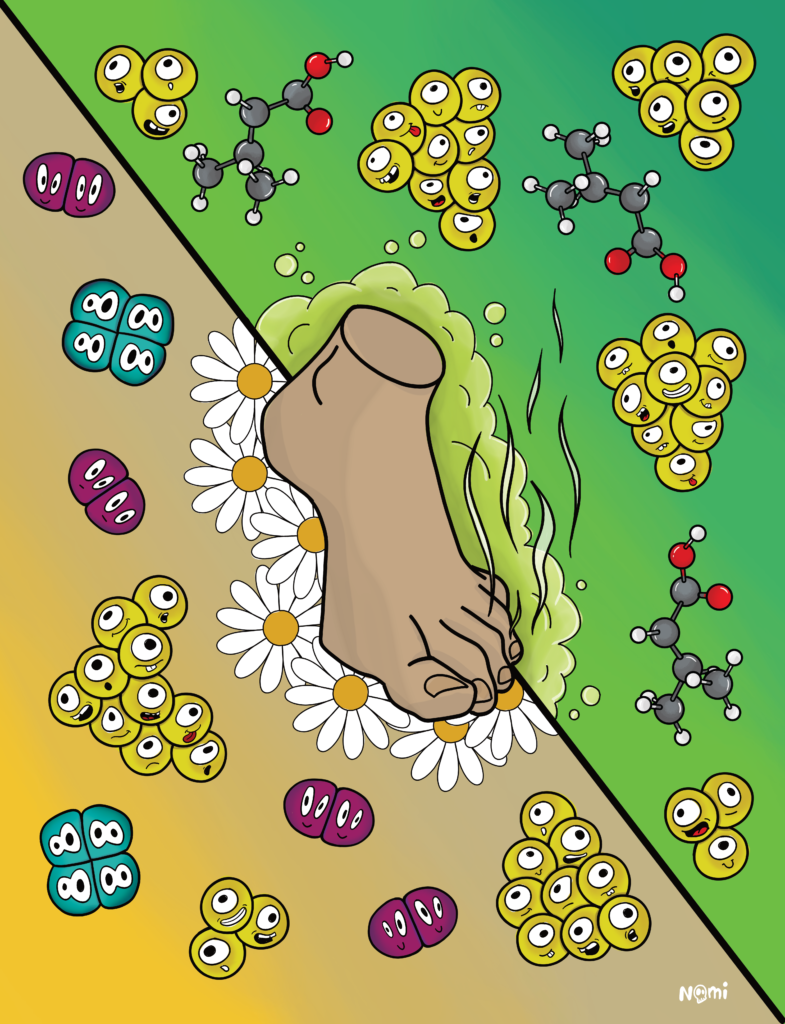

Bacteria are responsible for smelly feet

Another significant area of your body directly impacted by bacteria and their smell-creating superpowers is your feet.

Our feet actually contain the highest variety of microbial communities, with Staphylococcus, Corynebacterium and Brevibacterium being the most common. These bacteria feed on skin particles, urea and the amino acids in sweat.

For example, Staphylococcus epidermidis, a normal resident of human skin, degrades the amino acid leucine into isovaleric acid. Unfortunately, this molecule has a powerful, rancid cheese-like odour—the reason for smelly feet.

Fortunately, other bacteria, like Brevibacterium, Micrococcus and Kytococcus, can completely degrade both leucine and isovaleric acid, thus preventing the unpleasant smell. As usual, it comes down to having the friendly bacteria around.

Bacterial smells in your life

As we’ve seen, the world of bacterial smells is fascinating and complex. From the earthy smell of rain to the rancid odour of sweaty feet, bacteria play crucial roles in creating the smells that surround us.

These microbial odours are not just curiosities; they have important functions in nature and human biology. They can act as communication signals between microbes, influence animal behaviour, make our food smell delicious and even impact our unique body odour. So, embrace the microbial world with all its facets, colours and smells!