Imagine a bacterium in the environment finally having found a quiet corner to live in. This place has a lot of nutrients, delicious food and lots of space for the bacterium to settle down and relax.

How does this bacterium make sure it won’t be disturbed in its new quiet environment? Easy – it builds a house to protect itself and its siblings.

But a bacterial house is a special one – we call it a bacterial biofilm. And bacteria form a biofilm when they want to protect themselves from their surrounding, form communities and grow and reproduce.

Let’s read on to find out what these bacterial houses are and how they build them.

Why do bacteria form a biofilm?

Just like you need a roof over your head to protect yourself from the outside weather, bacteria form a biofilm that works like a house. And they build these houses from scratch.

A bacterial biofilm has protecting walls and a roof around it. These barriers defend them from all sorts of stresses of chemical or mechanical nature.

And there are so many advantages for bacteria to live in such a house:

- Most antibiotics cannot penetrate biofilm so that bacteria are safe inside.

- Bacteria keep their own nutrients and water and oxygen within the biofilm.

- In the case of desiccation or starvation, they can survive inside.

- Immune cells cannot break through a biofilm, hence bacteria inside are protected from the host immune system.

So, basically, a biofilm is the master accommodation for bacteria.

Where do bacteria form a biofilm?

Biofilm is the stuff that you can feel on your teeth in the morning after you woke up. But don’t worry, you easily brush it off your teeth.

Biofilm is the gloomy stuff that grows on your kitchen sponge and it is the crust in your kitchen sink if you haven’t cleaned it for a while.

Some bacteria can form a biofilm on contact lenses, which can lead to eye infections.

Unfortunately, bacterial biofilms are also one of the major burdens in hospital settings. Here, bacteria form biofilms on medical devices like catheters, joint replacements, implants or pacemakers.

Researchers even found microbial biofilms in 3.2 million-year-old fossils from volcanoes.

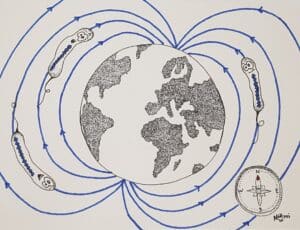

So, generally, bacteria can form a biofilm on any surface.

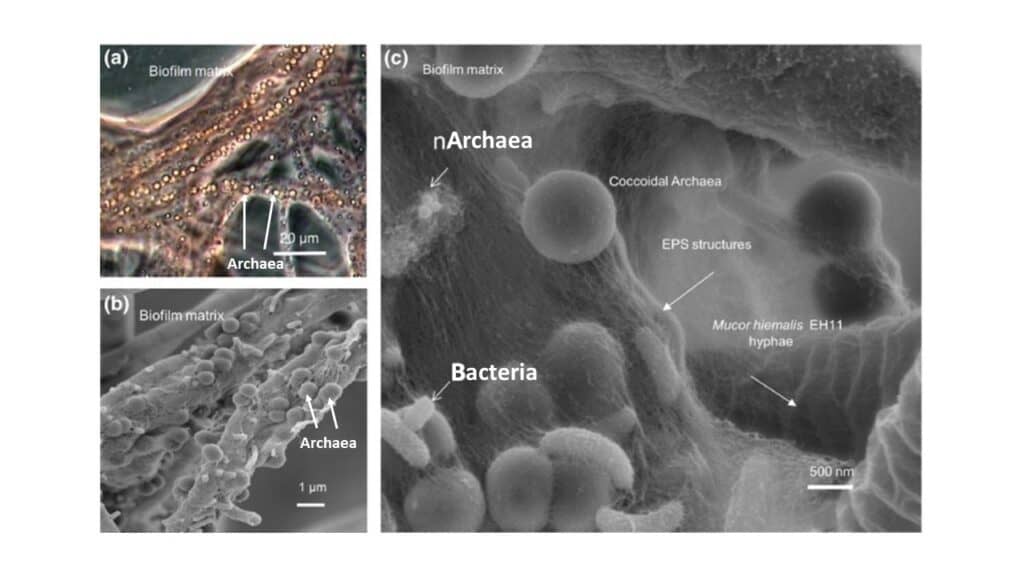

What does a microbial biofilm consist of?

Many microbes and especially bacteria can form a biofilm. And dependent on the microbial and bacterial species, the biofilm can have a different colour, thickness and texture.

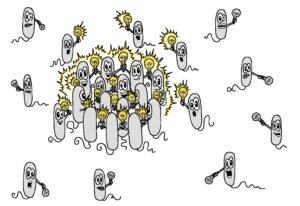

Generally, biofilms consist of bacterial cells (either only one species or many different ones), as well as other microbes as for example viruses or phages. All these microbes inside the biofilm talk to each other and communicate.

Inside the biofilm, bacteria glue themselves together with so-called extra-polymeric substances. These are big molecules that bacteria produce and excrete.

These extra-polymeric substances are proteins, lipids, sugar molecules or polysaccharides and DNA. And these substances give the biofilm its gloomy or slimy texture.

Interestingly, each microbe and bacterium produces a slightly different kind of polysaccharide. And each of these polysaccharides has slightly different chemical properties. This makes the texture of biofilms from different bacteria also slightly different.

Within the biofilm, bacteria can store everything, for example, metal ions bound to DNA, nutrients like sugar, bacteriophages, oxygen… And bacteriophages even protect the bacteria inside the biofilm.

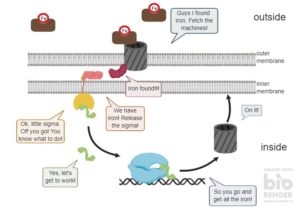

How do bacteria decide to form a biofilm?

This is an important question scientists are currently trying to understand. As soon as we understand how bacteria regulate biofilm formation, we might be able to develop drugs that prevent bacteria from biofilm formation.

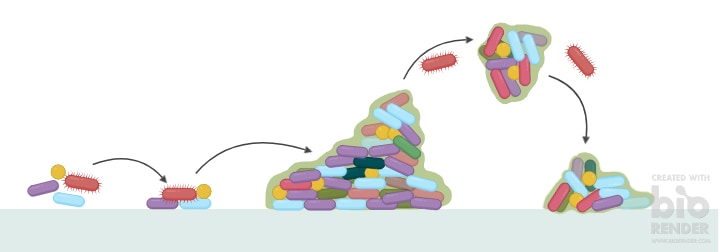

There is a general model of how bacteria form biofilm.

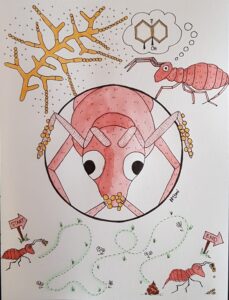

The general idea is that a few bacteria attach to a surface. For this, they use special adhesion proteins that help stick to the surface.

Now, bacteria want to settle down so that they do not need to move anymore. This is why they stop all movement mechanisms like swimming.

As mentioned already, inside the biofilm, bacteria talk to each other. Like this, they know when they are many together and they can start producing these extra-polymeric substances. By excreting them, bacteria get glued to each other. This helps them completely encapsulate themselves with this hydrogel.

Interestingly, once in a while, a bacterium spontaneously explodes. Then, the other bacteria use the cellular content (so all the DNA and proteins and lipids) of the dead bacterium to form more biofilm.

Inside such a so-called mature biofilm, bacteria happily grow and divide inside.

However, as soon as nutrients become scarce inside the biofilm, the bacteria need to find a new place to live. Then they will start producing scissors to break the biofilm. And when they activate their swimming and motility motors they can detach from the biofilm towards a new place where they start all over again.

How do we research bacterial biofilms?

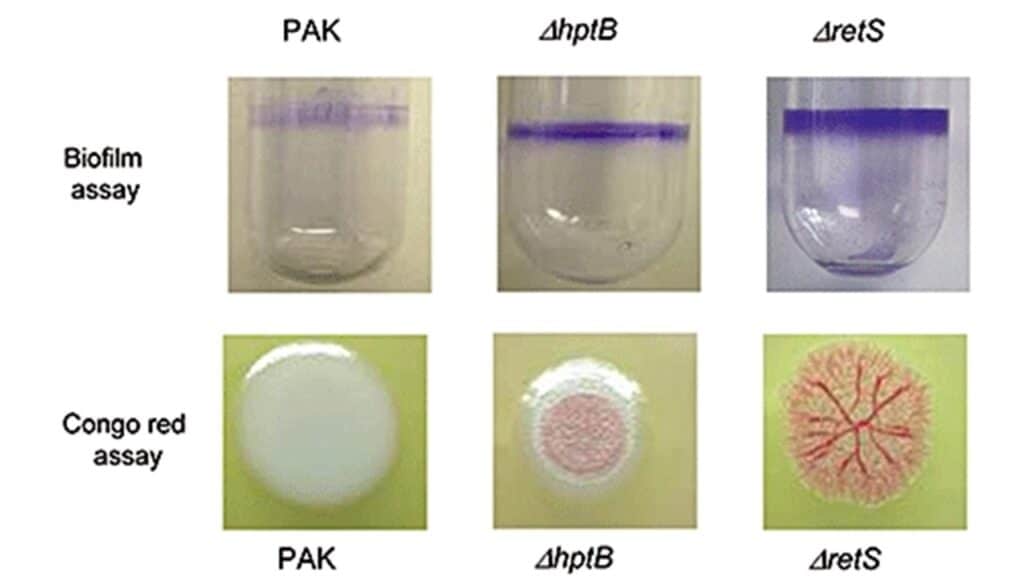

This is actually pretty easy, as there are many different stains that specifically bind to bacterial biofilm and make them visible. In the picture below you can see two examples.

These are two different stains that visualise bacterial biofilms. With the stain crystal violet, we can see a purple ring of biofilm on plastic and with congo red, we can visualise the structure of a biofilm.

In the above picture, in the left column (PAK) is a biofilm of the bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa. This one does not make much biofilm because you can barely see any violet or red stain. The other two columns are different mutants that produce more biofilm. These biofilms you can recognise by the strong violet or red colours.

With these experiments, researchers can understand under which conditions bacteria form more or less biofilm or whether their texture changes. This will eventually help us get a clearer picture of the fascinating life of bacteria and how to counteract them.

We still don’t understand biofilms very well. And so far we know that some enzymes exist that break a biofilm apart. However, the big goal would be to prevent bacteria from forming biofilms in the first place.

4 Responses

Are biofilms the reason why disinfectants kill only 99% of bacteria or because of other resistances, or both? Or are disinfectants actually an effective way of penetrating the biofilm and killing the bacteria inside?

That is a great question and I was just skimming through the current literature. It seems that bacteria grown in a biofilm are generally a lot more resistant to disinfectants than planktonic (swimming) bacteria. This is a major problem in hospital environments as it is super difficult to completely get rid of a bacteria once they have established a biofilm.