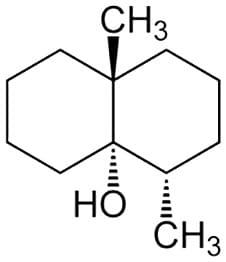

Can you imagine the refreshing and earthy smell of summer rain? This smell comes from a molecule that bacteria produce: geosmin.

Geosmin is one of these bacterial products that easily vaporise into the air and often have distinct smells. They are called volatile compounds.

Some other volatile compounds make the taste of chocolate or the smell of Cheddar cheese. And others, like geosmin, the smell of rain.

Bacteria produce geosmin – a volatile organic compound

Geosmin has this specific earthy or musty odour. It is the natural smell after a refreshing summer rain; the earthy smell of beets or carrots but also the off-tastes in water or wine.

You probably know what I am talking about.

Geosmin itself is not toxic, however, toxic fungi and bacteria produce geosmin. To our brain, the smell of geosmin signals that toxic fungi or bacteria are growing. So, our brain protects us from those by telling us not to eat the food. Thanks, brain!

Animals can also “smell” geosmin. For example, when the vinegar fly senses geosmin, it understands that toxic fungi are growing. In this situation, geosmin also acts as a repellent and the fly chooses not to eat or live around that place.

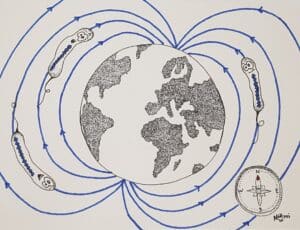

On the contrary, some mosquito species are attracted to the smell of geosmin. For them, the geosmin smell means that they are close to a lake, so the mosquito chooses to lay its eggs in the vicinity. Later, the mosquito larvae grow in that lake where they already have a food source. They will eat the bacteria. So, to mosquitoes, the geosmin smell is a sign of food.

Streptomyces – a geosmin producer

There are a few families of bacteria that produce geosmin. One of them is bacteria from the Streptomyces family. And Streptomyces already has a pretty interesting lifestyle.

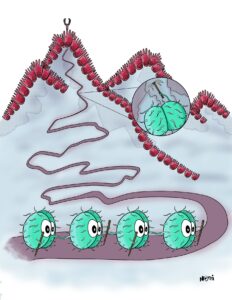

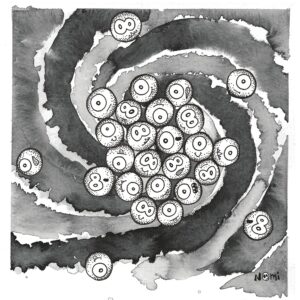

Streptomyces not only grows as a bacterial cell, but it also produces very long and thin arms that grow out of the bacterial cell; so-called mycelia. The mycelia from one bacterium form a connected network with mycelia from other bacteria. And this complex mycelia network can extend into the soil, spread around soil particles and even wrap around tiny organisms.

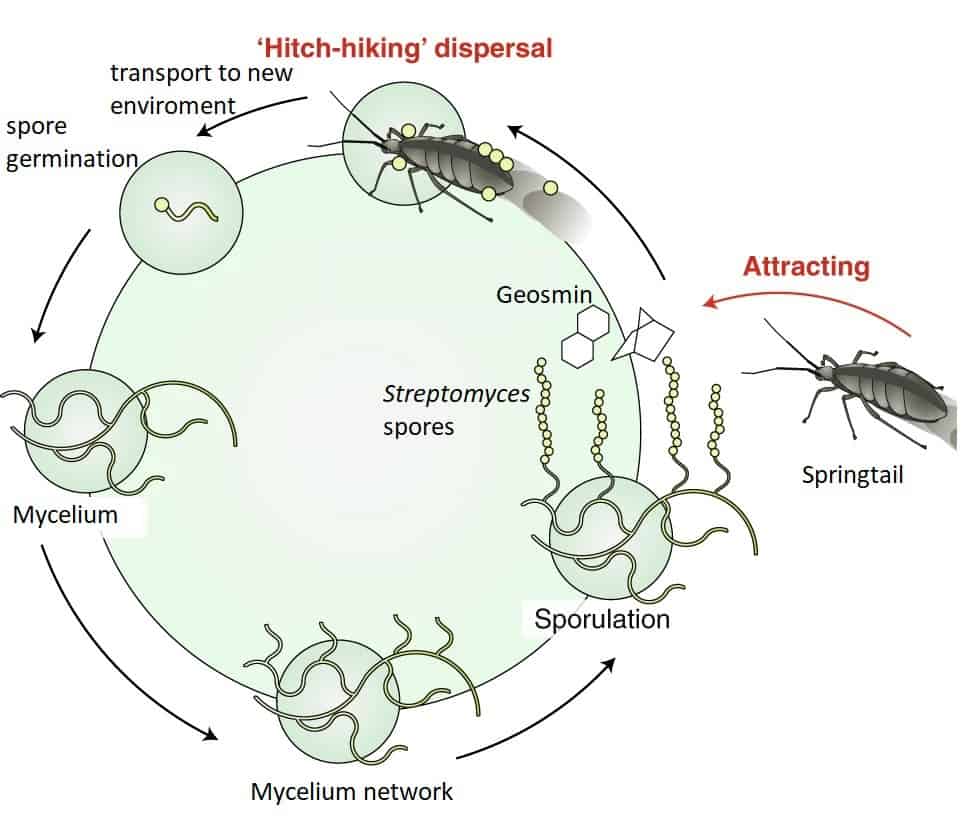

After forming an interconnected mycelial network, the Streptomyces bacteria produce spores. And interestingly, Streptomyces produces these spores at the end of the mycelia arms.

Bacterial spores are non-viable versions of bacterial cells, just like a plant seed is a non-viable version of a plant. Spores generally only contain the genomic DNA of the bacterium, proteins to stabilise the DNA and proteins to react to the environment.

Similar to plant seeds, spores are wrapped in a thick envelope to protect the spore from the surrounding. Then, when the environmental conditions are better, the spore – just like the plant seed – germinates and forms a viable bacterial (plant) cell. This cell can then grow and metabolise and form new mycelia.

Why do Streptomyces bacteria produce geosmin?

Interestingly, when Streptomyces starts forming spores, the bacteria also produce geosmin.

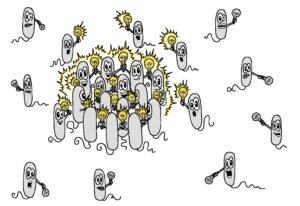

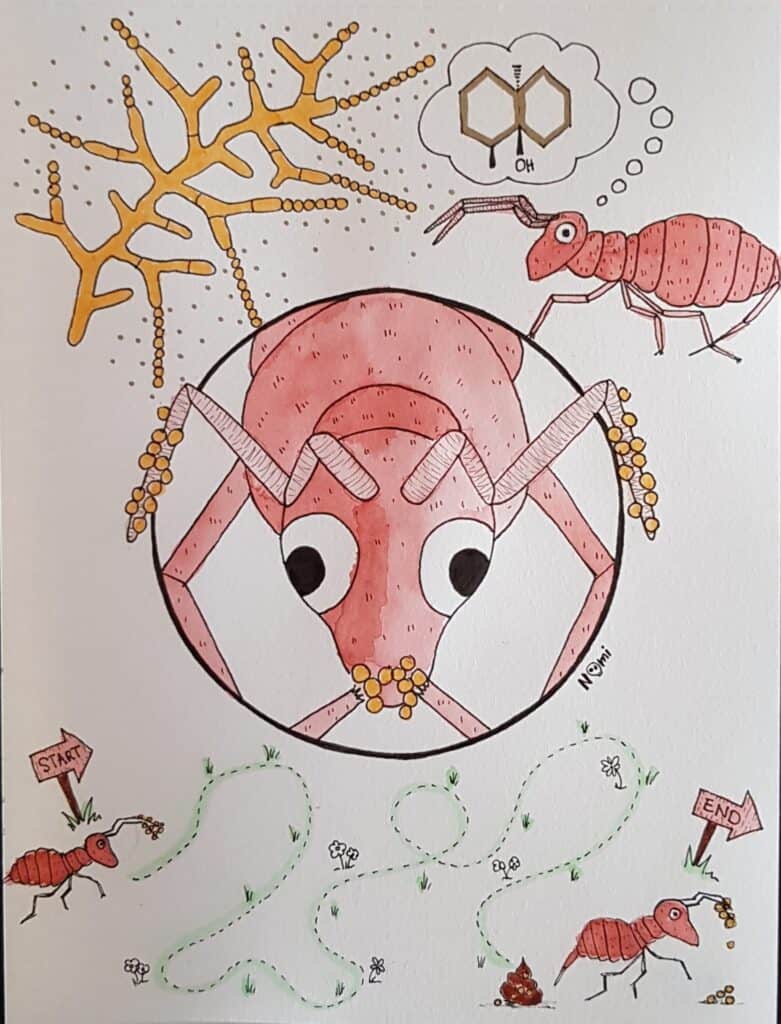

Research found that a little insect-like animal, the springtail, is actually attracted to geosmin-producing bacteria. These tiny invertebrates – also known as snow flies or Collembola – live in the soil. And here, they are especially attracted to Streptomyces spores.

Researchers saw that the springtail uses its tiny antennae to smell the geosmin. The insect then follows the geosmin smell and once it found the Streptomyces spores, it starts eating them.

What is the advantage of being eaten by springtails?

Yes, it seems that bacteria produce geosmin to attract animals and insects to be eaten by them. To understand the reason for that we have to know that the springtail is covered with a waxy outer layer. Spores, on the other hand, have a hydrophobic envelope that easily sticks to the waxy springtail. This makes the spores stick to the springtail.

And when the animal moves around in the environment, it carries the spores around. So, it seems that bacteria use the animal as transport vehicle.

Also, the researchers saw that the springtails absolutely love eating those Streptomyces spores. They even found that the spores are not digested by the springtails. Instead, the springtails had viable spores in their faeces from which the bacteria could grow again. This finding gave the researchers another clue that Streptomyces spores might use the animals for transport.

So, it seems that Streptomyces bacteria produce geosmin to attract insect-like animals to attach to them and use them to hitchhike to different places. In a new place, there might be more nutrients for the spores to germinate, form viable bacteria, grow and reproduce.

From this, the cycle starts over again, as the bacteria form mycelial networks again to produce spores. Then, the bacteria produce geosmin to attract insects to get carried somewhere else again.

Bacteria live with many more players in the environment

Yet, one thing to take into account at this point:

Both Streptomyces and springtails live in the soil and in this study, the researchers only looked at how these two species interact with each other.

In the soil, there are several other bacteria, fungi, viruses, insects or tiny animals. So far, we have no idea about how any of these other organisms could impact the interaction between Streptomyces and springtails. The researchers did this study in the controlled environment of the lab. But the whole game might completely change in the wild environment of the soil.

However, I still think this is a cool example of how bacteria trick animals for their own good.

Take away from this article:

- Bacteria produce volatile compounds like geosmin that animals can taste or smell and be attracted to or repelled from

- Bacteria specifically produce geosmin to attract springtails to eat the bacterial spores

- Springtails transport the bacterial spores to new places