There are ten times more phages on this planet than bacteria. And since the main aim of phages is to spread their genomic information into host cells, they have a huge impact on microbial ecology and evolution.

Phages are basically genomic information – DNA or RNA – within a lipid-protein shell. Distributing their DNA or RNA into as many hosts as possible allows the phages to survive. They then reprogram the host to produce more phages packed with more phage DNA or RNA.

These newly produced phages then trigger the host to release themselves which can even kill the bacterium. With the release, the phages are spread further into the surrounding until they encounter another host and the cycle begins again.

Of phages and bacteria

Many different bacteriophages exist that specifically infect certain bacteria. So, just as their hosts differ, the phages differ as well. They come in different shapes, sizes and reproductive mechanisms.

Some phages have very simple shapes as in the picture below. Here, we will focus on the filamentous phages that can be even longer than the host bacterium itself.

Filamentous phages are very common in bacteria and they also have a special ability: They program the bacteria in a way that bacteria do not always produce the phage. They control the bacterium and wait until the right moment comes for them to be produced.

This means that these bacteria have DNA of the phages inside their own DNA. And only when the phage DNA is activated, the bacteria actually produce the phages. Until then, the phage is a so-called silent phage within the bacterium.

Let me be your phage

One bacterium that is infected with a silent phage is the pathogenic bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Within its genome, Pseudomonas aeruginosa contains the DNA for the filamentous Pf4 phage. However, it only produces this phage when the bacteria live in a biofilm community.

So, it seemed that the phages must somehow help the bacteria in the biofilm. As a new study found these phages actually help the bacterium become more resistant to antibiotics and chemical and toxic substances inside the biofilm.

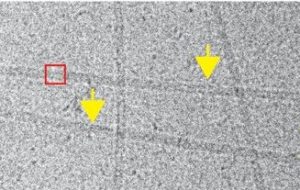

But the way the phages achieve that is a fantastic antibiotic resistance mechanism that was not known before. To learn about the strategy, researchers took images with the microscope of the Pf4 filamentous phage. And they found these long phage filaments.

I wrap around you

While these structures were pretty impressive, they didn’t explain how the phages would actually behave within the biofilm together with Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

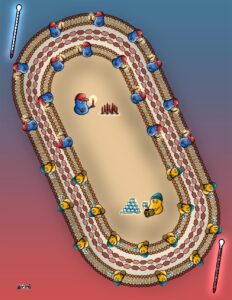

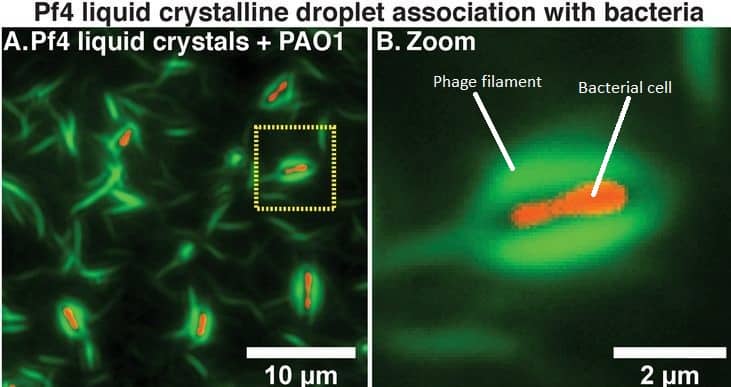

So, the researchers added some artificial biofilm from the bacterium to the phages. They then looked at the phages again in the microscope and they saw that the phage assembled and formed ordered filaments. These looked like highly organised nets of phages.

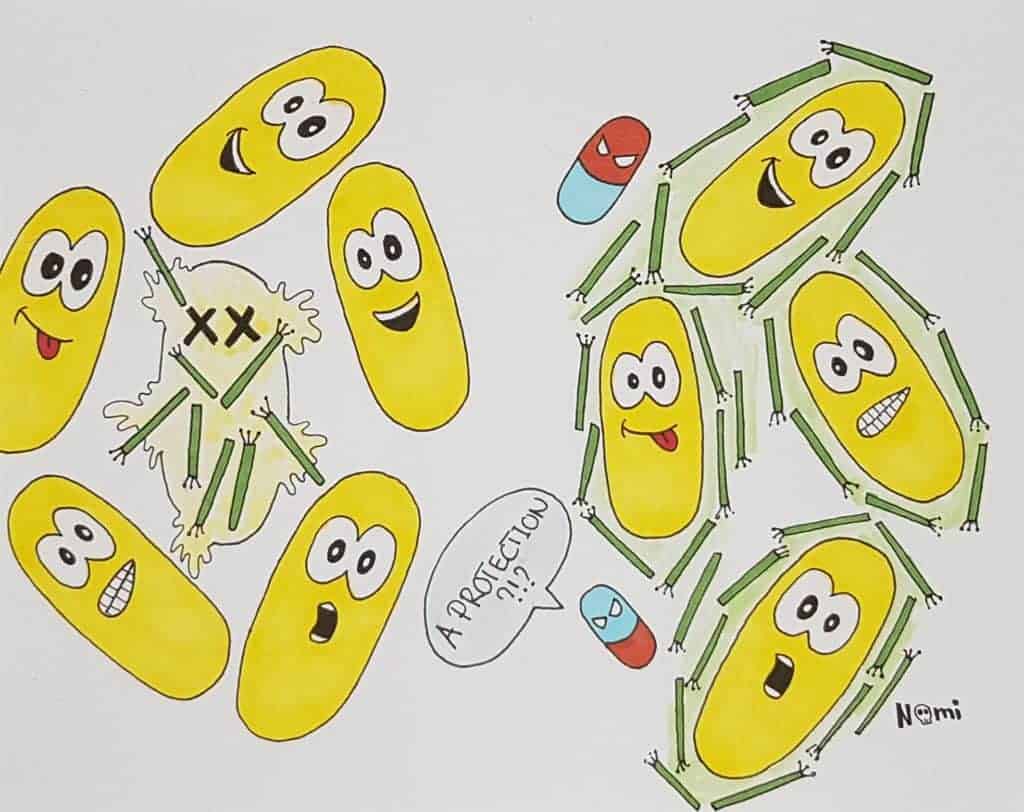

I protect you

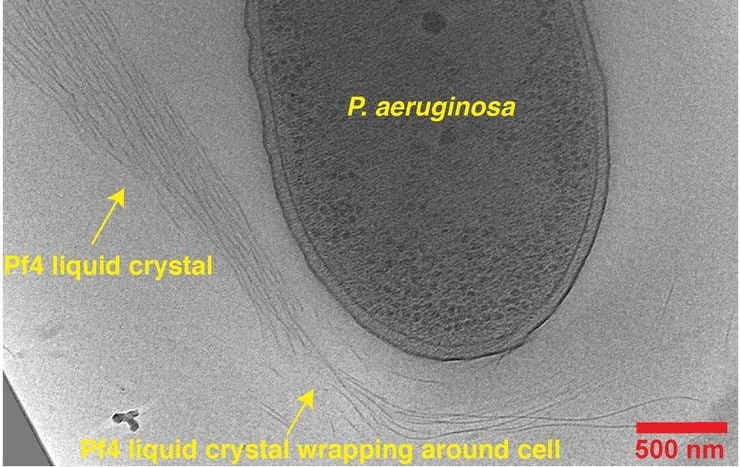

The researchers then wanted to see how the bacteria could fit into these nets. So, they took images of the phages together with the bacteria. And they saw that the phages form their nets close to the bacterial cells just as in the picture below.

It seemed that the phage nets wrapped closely around the bacterial cells. Like this, the phages would form a droplet shape around the bacterial cell and separate it from the surrounding.

And these droplets are the foundation for the resistance to antibiotics of the bacteria. When researchers added different antibiotics to the phage-bacteria-droplets, the bacteria survived.

On the contrary, the bacteria on their own were dying from the antibiotic attack.

This means, that the phage net works as a wall to protect the encapsulated bacterium from toxic molecules in the surrounding. This is a completely new and remarkable mechanism of bacteria to protect themselves from environmental dangers. And they use their very own phages to do that!

It seems that another race against antimicrobial resistance just started…

And then I start again

Let’s put it all together and have a look at the life cycle of these phages:

Pseudomonas aeruginosa carries genes for the Pf4 phage in its genome and only activates them when it grows within a biofilm. At this moment, Pseudomonas produces both biofilm material and the Pf4 phage. These released phages then form nets around the bacterial cells. With this net, the phages protect bacteria from antibiotics and other toxic substances.

So, it seems that phages protect their own hosts from environmental dangers. After having hijacked the bacteria’s cell for their own production, it’s actually a pretty nice thing to do.