Just as you might invite yourself over to your friend’s house when you’re hungry, bacteria are sometimes nice to each other and feed each other.

And this food exchange is what makes bacteria and their interactions so incredibly fascinating. Bacteria can fight each other to get rid of competitors or they are nice to each other and share food.

But how do bacteria feed each other? How do they know that they have a friend in need of food? And how do they actually exchange the food?

Read on to find out how.

How bacteria make stuff

First, we need to understand how bacteria actually produce stuff and what proteins are made of.

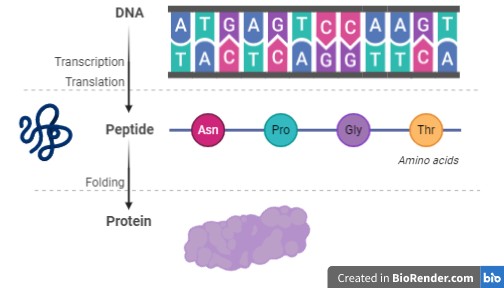

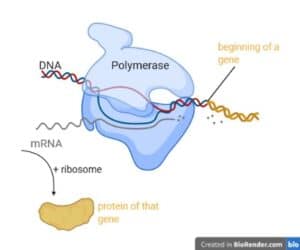

Bacteria and all living organisms use their DNA as a transcript. They read this transcript and produce long chains of amino acids from it. This chain is what we call a peptide. And this peptide eventually folds into a protein.

Most organisms use twenty amino acids to make their proteins. And since these amino acids can link together in any random distribution, proteins can look completely different. They have all sorts of different sizes, shapes, functions, binding sites, etc.

Now, these amino acids are like LEGO bricks that can be linked together in a million different ways and the outcome is always different (which is why proteins are so different). To produce all the necessary proteins, each amino acid needs to be present within a cell.

But not all organisms can produce all amino acids. For example, we need to make sure that we take up certain amino acids with our food since we cannot make them ourselves. Similarly, some bacteria need to find certain amino acids in their environments to make all proteins so that they can function properly.

How bacteria feed each other

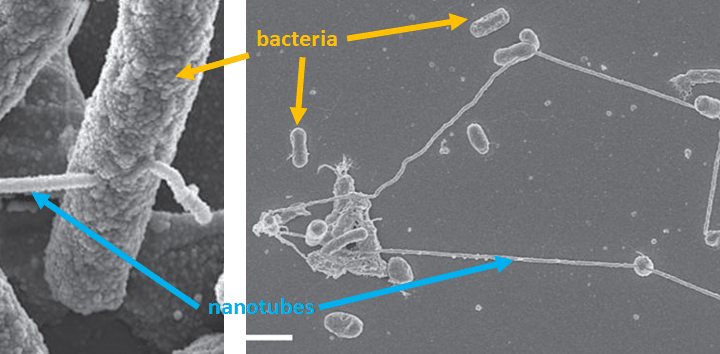

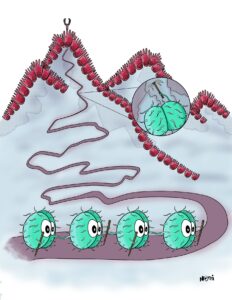

A new study found that some bacteria can actually help each other when one of them is in need of a specific amino acid. In this case, the bacteria form tubes between them to exchange cellular content. These tubes are called nanotubes and bacteria use them to exchange nutrients to ensure the receiving cell survives.

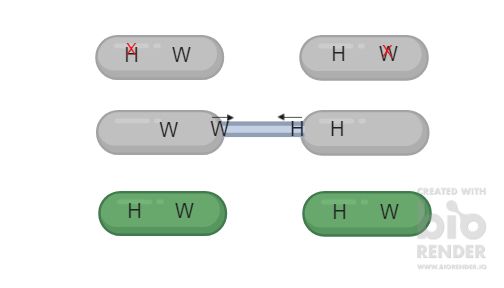

To better understand this sort of food exchange, the researchers used the idea that bacteria need all of the amino acids to survive. So, they wanted to show that two different bacteria can help each other out with certain amino acids. For this, they created two bacteria with different abilities – so-called strains:

- one strain produced a lot of amino acid W and no amino acid H

- the other produced a lot of amino acid H and no amino acid W

W and H are the codes for the two amino acids Tryptophane (W) and Histidine (H).

In the experiments, the researchers then grew the bacteria in a medium that did not contain the amino acids W and H, but all the other ones. They grew the bacteria:

- together so that they would be in close contact

- together but with a separating “wall”

- on their own

Neither of the bacterial strains could survive on their own as each was missing one amino acid. Also, when the two bacterial strains grew in the presence of a wall, neither of them survived.

Interestingly, only when they grew closely together, did both bacteria survive. This meant that the two bacteria needed to have direct contact with each other to survive. Also, the survival of both bacterial strains completely depended on each other.

Bacteria form nanotubes to feed each other

When the scientists then took a closer look at the bacteria, they saw that the bacteria formed some kind of nanotube between the cells. And they are convinced that the bacteria use these nanotubes to exchange nutrients and feed each other with essential food.

It is as if you and your neighbour both want to make a cake but they miss the eggs and bought too much flour while you forgot to buy flour and got too many eggs. Neither of you would be able to make the cake on your own. So you need to dig a tunnel between your flats to exchange eggs and flour and you can both bake your cakes.

However, now the interesting question one might ask is how do you know that your neighbour needs eggs and how do they know that you have enough to share? You cannot just start digging a tunnel hoping that your neighbour has the things you need.

So how does one bacterium know that the other one is in need of a certain amino acid? We know that bacteria do talk to each other, but they certainly will not call or send the other guy a message on WhatsApp…

And also, what is it that the bacteria actually exchange? Do they send the amino acid itself (hence the eggs) or do they send the DNA so that the other cell can learn how to make the amino acid? This would mean you send your neighbour a chicken so they can produce their own eggs…

We now better understand how bacteria can feed each other and make sure their friends survive. Yet, there are still many unanswered questions about this interaction. Hopefully, we will have some answers to them soon.

7 Responses

Interesting stuff! ? In theory, would it be possible to send modified or even artificial bacteria to the real ones? In that case, they could surely transfer some DNA or molecules that weaken the real bacteria.

Glad you liked it! I’m pretty sure they’re already testing that somehow… ?

Question: if the two bacteria have both the amino acids they need, would they build those tubes anyway? Or they just build them when they need to exchange something?

The exchange is strictly linked to the demand of a given bacterium. So only when they starve for certain metabolites (e.g. amino acids), they would establish these connections. In case bacteria do not starve and grow autonomously, they do (normally) not establish tubular conections to other bacterial cells. Hope this answers the question.

Yes, perfect! Thanks

Do you have anything about resistance ?

Hey Roger, thanks for your interest.

Yes, there is a compilation of articles about antimicrobial resistance on https://sarahs-world.blog/tag/antimicrobial-resistance/

Hope it helps.

Sarah